Theories of international trade: from Old Trade Theory to New-New Trade Theory

Evolving world trade theories: from classical ones to new business-focused paradigms

Published by Silvia Brianese. .

Export Foreign markets Internationalisation Planning Import Internationalisation toolsOne of the most strategic decisions for a business is to start a process of internationalization. To make this decision, the business must first have reached the awareness of:

- being able to be competitive in foreign markets;

- being able to gain benefits from internationalization.

While the answer to the second question is quite obvious, as the benefits gained from internationalization consist of a dimensional growth of the business and a reduction in market risk thanks to geographical diversification; the answer to the first question requires further analysis. To this end, it may be useful to analyze theories on foreign trade and gather useful insights for the decision to embark on a path of internationalization.

Since the time of Adam Smith and Ricardo, fathers of classical economics, economists have questioned the reasons that drive countries to exchange goods and services with each other. Starting from the foundations laid by David Ricardo with the theory of comparative advantage, theoretical models on the functioning of international trade have progressively incorporated new hypotheses to better explain global trade dynamics. Since the 1990s, the focus has increasingly shifted from a macro level to a micro one, focusing on businesses, the true protagonists of trade, and on the interaction between their specific characteristics and export activities.

The purpose of this article is therefore to illustrate the path that led to the emergence of the so-called “New-new trade theory” and how it has revolutionized the study of international trade.

The Classical and Neoclassical Theory of International Trade

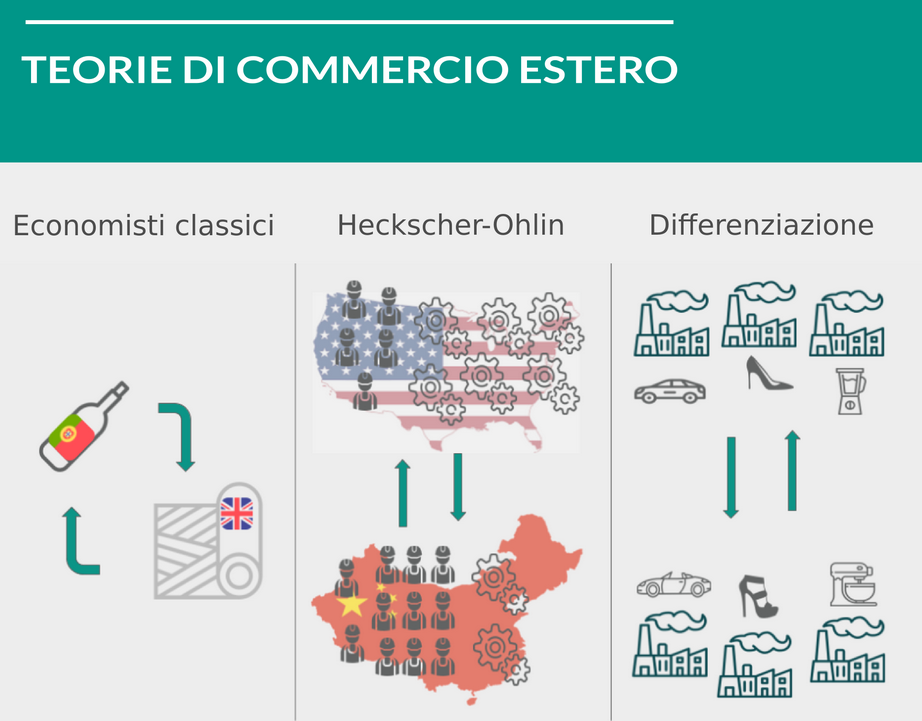

The models of Ricardo (1817) and Heckscher-Ohlin (1919 and 1933), pillars of the classical and neoclassical theory of international trade, are based on the concept of comparative advantage to explain the exchange of goods between countries[1]. The Ricardo model argues that countries tend to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage in production compared to other countries (the famous case of the comparative advantage in wine production in Portugal, compared to that of England in textiles, is often cited). Economists Heckscher and Ohlin expand on the conclusions of the Ricardian model, suggesting that countries are characterized by different availability of resources used in production (capital and labor), and therefore will specialize in the production of those goods that intensively use the factor of production they have in abundance.

However, these models, focused exclusively on exchanges between different sectors (inter-industry trade), fail to explain why a large part of international trade occurs between countries similar in factor endowments and within the same sectors (intra-industry trade). This limitation led to the development of “new” models, such as those by Krugman (1980) and Helpman-Krugman (1985), which, by including economies of scale, product differentiation, and imperfect competition, laid the foundations of the new international trade theory, known as the New Trade Theory. More recent theories indeed show that even countries identical in technology and factor endowments can benefit from trade liberalization if they exchange differentiated goods. Differentiated products possess individual characteristics such that, although they have similar features to other goods, they are not considered perfect substitutes by consumers. A classic example of this is clothing or automobiles.

Formally, there are two approaches to explaining consumer demand for differentiated products.

- Love for variety: each consumer prefers a market where a greater variety of the same type of good is available;

- Ideal variety: the assumption behind this approach is that each product has a different set of characteristics (shape, color, material, etc.). Consumers will choose the good closest to their ideal variety, and the market will support multiple firms providing similar products.

The Presence of Firm Heterogeneity and the New-new Trade Theory

Previous models have generally assumed competition in global markets as a comparison between countries, overlooking the crucial role of firms as the main drivers of import and export flows. Moreover, both in classical and modern international trade theory, the assumption of a single representative firm for the entire economy has often been adopted. While this simplification is useful for general equilibrium analysis, it does not reflect reality, as firms within the same industry can vary significantly in terms of productivity, capital, and skills. Thus, starting from the Bernard and Jensen model of 1995, a new perspective for the study of international trade emerged: using firms as the unit of analysis instead of countries, the so-called "New-new trade theory" was outlined. This theory, which focuses on the variety among firms within industries, was further developed in the 2000s with the models of Melitz (2003), Helpman et al. (2007), and Bernard et al. (2007).

The inclusion of the hypothesis of firm heterogeneity in international trade models has provided significant insights into how firm characteristics influence export activities. Using firm-level data from the U.S. manufacturing sector, Bernard and Jensen (1995, 1997, and 1999) identified significant differences between exporting and non-exporting firms in terms of size, productivity, capital intensity, technology, and wages. By integrating the hypothesis of firm heterogeneity into Krugman's 1980 intra-industry model, Melitz in 2003 developed a model to explain why only a few highly productive firms engage in export activities. These firms are able to generate sufficient profits to cover the fixed costs of entering international markets. This leads to a “self-selection” effect, determining which firms will become exporters in each sector.

In particular, the Melitz model assumes that firms within a sector operate in a context of monopolistic competition, offering horizontally differentiated products. To start production in the domestic market and enter foreign markets, firms must incur fixed costs, which then become sunk costs. This results in two main consequences:

- firms with productivity below a certain threshold cannot cover production costs and are therefore forced to exit the market;

- export activities are carried out only by firms that manage to overcome the entry barrier to international markets.

When new firms with higher productivity levels than those already active enter international markets, the required productivity threshold increases, forcing less productive firms to exit. This “self-selection” mechanism and the reallocation of resources toward more productive firms demonstrate that trade liberalization can increase sector productivity. In fact, a reduction in global trade barriers would increase the profits of exporters and lower the productivity threshold required to export. This would lead to an increase in exports, a higher demand for labor, and an increase in the prices of production factors, reducing the profits of non-exporting firms. Consequently, less productive firms will exit the market, while the transfer of resources to more productive firms will improve aggregate productivity.

Conclusions

While the Old and New Trade Theory primarily focused on differences between countries in terms of resource endowments or technology, assuming that all firms within a sector were homogeneous, the New-new trade theory marked a significant advancement in understanding international trade. By focusing on firm heterogeneity within sectors, this theory has provided a better understanding of the factors that influence firms' competitiveness and export capacity. This progress was also made possible by the growing availability of firm-level data, which has allowed for more precise analysis of trade dynamics and the identification of causal relationships that would have remained hidden in an analysis based on aggregated data.

Finally, the analysis of the illustrated economic theory highlights two main points useful for evaluating the decision to embark on a path of internationalization:

- firms that produce goods with local specialization (due to product characteristics, process, or inputs), if they are competitive in the domestic market and if there is demand for that product in foreign markets, are likely to be competitive in foreign markets as well.

- if the firm does not have comparative location advantages, it must have reached an adequate level of productivity to internationalize and should base its positioning in foreign markets by implementing differentiation strategies.