Challenges and changes in global trade

Fragmentation of trade, tariffs, and implications

Published by Marzia Moccia. .

Macroeconomic analysis Economic policy Global demand Importexport Global economic trends

In recent years, the global trade of goods has undergone significant changes.

One of the most relevant topics today, to read, outline, and anticipate future trajectories of world trade, undoubtedly concerns the debate on the future of globalization.

In light of the promises made during the American electoral campaign, primarily on the Republican side, the hypothesis of a future characterized by increasing fragmentation of trade is becoming more solid, driven by geopolitical and strategic motivations rather than mere economic and productive convenience.

After years of shocks, including the COVID-19 pandemic, Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and the outbreak of conflicts, major global economies have begun to evaluate their trade partners based on geopolitical and national security implications. This aspect affects not only the trade flows of goods but also foreign direct investments and, consequently, decisions on production location worldwide. The reorganization of international trade along geopolitical lines, with an increasingly clear distinction between West and the Rest, presents the prospect of a world that is increasingly fragmented on the economic and political fronts.

Global Trade and Slowbalisation

If we frame these dynamics in a long-term historical perspective, it becomes evident that the shift in the pace of globalization on the world stage has been apparent for several years. The age of globalization has indeed given way to what the International Monetary Fund has dubbed slowbalisation, a slowdown due to the growth of protectionist measures, the US-China trade and technology war, and, more generally, the deterioration of geopolitical relations.

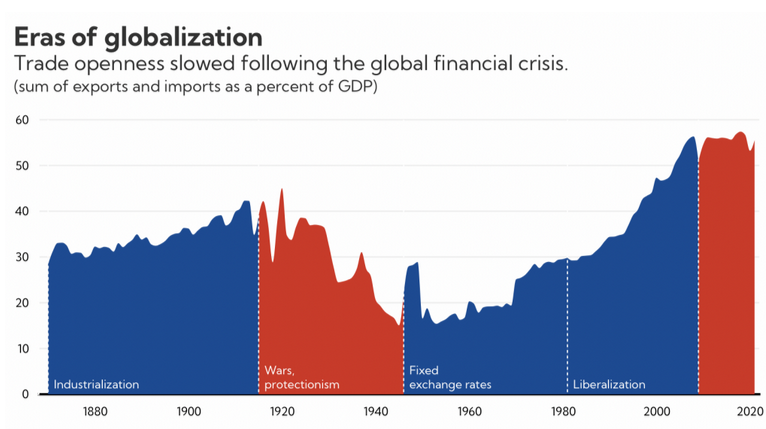

According to the International Monetary Fund, as depicted in the proposed chart, the history of globalization has been characterized by five main periods, each distinguished by different economic and financial configurations governing trade between countries.

From 1870 to 1914, the era of industrialization saw an expansion of global trade, dominated by powers such as the United States, Europe, Argentina, Australia, and Canada. This period was characterized by the “gold standard” system, which facilitated trade between countries, and technological advances in transportation, which reduced trading costs and increased the volume of flows. Between 1914 and 1945, due to the two world wars and the rise of protectionism, there was a reversal of trends. Conflicts and trade fragmentation led to increasing regionalization of trade. Despite efforts by the League of Nations to promote multilateralism initiatives, trade was severely hindered by existing protectionist barriers. From the post-World War II period to 1980, the world economy was shaped by the Bretton Woods system. The United States emerged as the dominant economic power, and post-war recovery in Europe and Japan, along with trade liberalization, fostered the resumption of global economic expansion. However, the period from 1980 to 2008 marked the most significant phase of liberalization (also referred to as “hyper-globalization”).

Moreover, emerging economies, such as China, gradually began to remove trade barriers, promoting increasing international economic cooperation. The founding of the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 helped manage trade agreements and resolve disputes, while cross-border capital flows increased, integrating the global financial system. The removal of trade restrictions and the globalization of production boosted the expansion of goods and capital flows on a global scale.

However, the 2008-2009 financial crisis marked the beginning of the so-called slowbalization, a phase of globalization slowdown: increasing constraints on further trade reform and liberalization emerged, political support for free trade weakened, and geopolitical tensions rose.

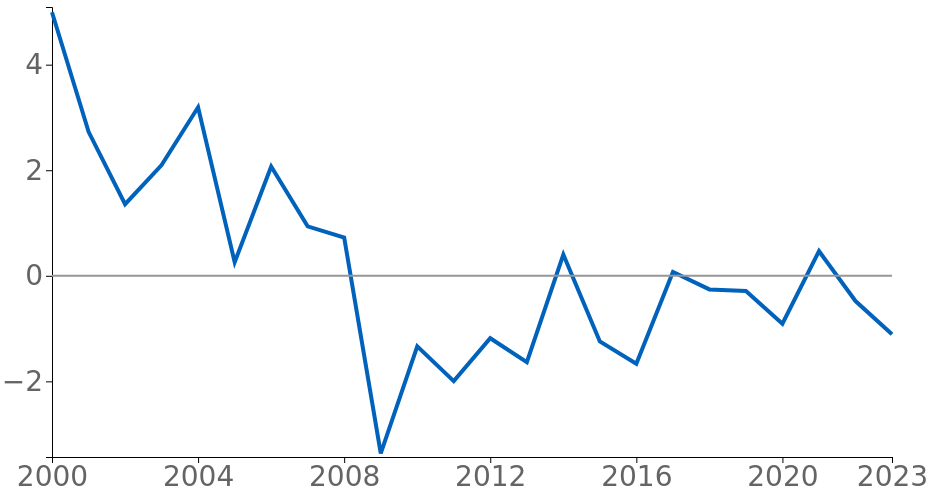

Focusing specifically on the dynamics of the last century, it is possible to document the progressive reduction in global trade elasticity to GDP starting from 2010: in particular, it remained significantly above 1 until the Great Recession, after which it flattened close to zero, with the last two years even falling into negative territory.

World Trade Elasticity to GDP

Source: ExportPlanning

Current Challenges and the Crisis of Multilateralism

In this scenario, rather than de-globalization, it would be more appropriate to speak of slowbalisation, which will increasingly incorporate the effects of a reorganization of trade between geopolitically aligned areas and a new international configuration in the coming years (think, for example, of the decoupling between the United States and China). However, another side of the growing fragmentation is the increasing political focus on protectionist measures.

Recently, the phenomenon of protectionism on a global scale has gained much attention, especially in light of the massive tariff plan announced by the US presidential candidate Donald Trump. This plan would impose a 10% tariff, up to a maximum of 20%, on all American imports from abroad, in addition to the 60% tariffs on US imports from China, even suggesting replacing federal income tax with tariff revenue. This measure almost “echoes” what was experienced in the early 1900s, as previously summarized.

The economic implications of implementing such a plan would be enormous. Several economists have estimated the costs of such a maneuver on the American economy (see for example Trump's bigger tariff proposals would cost the typical American household over $2,600 a year, Can Trump replace income taxes with tariffs?), however, an equally relevant aspect of this scenario relates to the possible international configuration that may result from it, given the possible tariff countermeasures from other countries.

As illustrated by the case of steel tariffs, particularly in hot-rolled coils, the protectionist tariffs introduced by Trump led - first – to the adoption of safeguard measures by the EU and, more recently, in response to the global oversupply, to protectionist actions by other major steel-producing countries.

The overall effect, following what has been a so-called “domino effect” on a global level, has been a loss of efficiency in global steel production, resulting in higher costs for user industries.

As discussed in the article Advantages and Costs of international Trade Liberalization, according to economic theory, a more fragmented system implies:

- a reduction in productive efficiency linked to specialization

- a reduction in economies of scale

- a reduction in the degree of competition and diffusion of know-how

This results in a less efficient competitive system, with higher costs for consumers who would face higher prices—stemming from a less efficient production system—and a lower availability of goods.

Naturally, the scenario of a “total return to protectionism” appears to be the one with the most negative consequences for the global economy, but it is now widely accepted that global trade is evolving towards a new configuration. In other words, the future will be one of “de-risking,” a strategy strongly supported by the EU, if not of “decoupling,” a strategy more accredited on the American front.