Recession averted and weak growth: a look at the latest numbers from the International Monetary Fund

Published by Alba Di Rosa. .

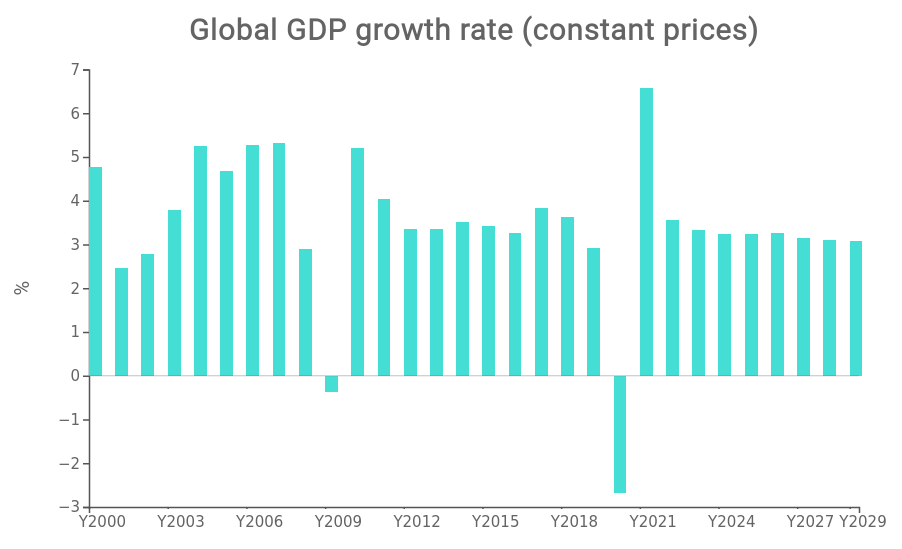

IMF Europe Macroeconomic analysis Uncertainty United States of America Emerging markets Global economic trendsAccording to the latest edition of the World Economic Outlook, released by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in October and available in the Analytics section of ExportPlanning, the growth of the world economy is proving stable, albeit disappointing in terms of performance. A growth rate of 3.2% for both 2024 and 2025 is confirmed for global GDP, in line with the latest editions of the study. Undoubtedly successful is the resilience of the world economy and its ability to avoid a recession, despite the significant and synchronised process of restrictive monetary policy in recent years in much of the world.

Alarm bells for the Fund, however, concern the growth outlook: five years from now, projected world GDP growth remains stable at 3.1%, which is mediocre compared to the pre-Covid average (3.7% over the period 2000-2019), as well as to the pre-pandemic forecasts, and suggests that potential growth may have been hit hard. Multiple structural challenges weigh on growth, such as an ageing population, weak investment and historically low total factor productivity growth.

Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2024.

Despite the apparent stability of the latest estimates of global GDP dynamics, there were in fact divergent revisions at the country level. The Fund highlights, in particular, upward revisions for US growth, which offset downward revisions for the largest EU countries. US economic growth for 2024 is now projected at 2.8%, an increase of 0.2 p.p. compared to the July scenario, due mainly to the performance of consumption and non-residential investment, before slowing to +2.2% in 2025.

Much more modest is the growth scenario for the Eurozone which, after bottoming out in 2023 (+0.4%), is expected to accelerate modestly in 2024 (+0.8%) and 2025 (+1.2%). The IMF estimates a positive contribution of exports to Eurozone growth in 2024, while domestic demand will support growth next year, in a context of gradually increasing real wages.

A point of focus for the Eurozone is the persistent weakness of the manufacturing sector, which is weighing on economic growth in countries such as Germany and Italy. However, while Italian domestic demand should benefit from the effect of the NRRP, Germany is suffering from the strains of fiscal consolidation and the sharp fall in real estate prices.

Source: StudiaBo elaborations on Eurostat data.

More dynamism comes for emerging and developing countries, whose GDP is expected to grow by 4.2% in both 2024 and 2025. Among these, India's buoyant growth is slowing down: after +8.2% in 2023, it will reach +6.5% in 2025, as pent-up demand accumulated during the pandemic is gradually depleted. A more gradual slowdown is expected for the Chinese economy, falling from 5.3% in 2023 to 4.5% in 2025. Weakness in China's real estate sector and low consumer confidence persist; on the other hand, better-than-expected net exports will contribute positively to growth in 2024.

On the price front, global disinflation is proceeding, without bringing a recession with it; on average 2024, global inflation is expected to reach 5.8%, to be followed by 4.3% in 2025 (progressively declining from 6.7% in 2023 and a peak of 8.6% in 2022). Inflation levels reached in 2022 were the highest since ‘96, reflecting the unique combination of several shocks: large supply disruptions combined with strong demand pressures after the pandemic, followed by sharp hikes in commodity prices caused by the war in Ukraine.

To date, inflation is approaching central bank targets in many countries, opening the door to rate cuts (started in June in the Eurozone, in September in the US). Advanced economies are proving faster than emerging economies in the price normalisation process, and are expected to reach their inflation targets sooner than the latter. For the average of advanced economies, inflation is expected to stabilise at 2% by 2025, and monetary policy is expected to return to a neutral stance.

While the global battle against inflation can therefore be said to be largely won, there is no shortage of possible surprises in the price adjustment process: the Fund reports, in particular, a stabilisation for goods prices, while inflation on the services front remains high in several regions.

"Brace for uncertain times"

The risks to the global economic scenario just described remain tilted to the downside, in a context of high policy uncertainty. The risks relate to possible increases in financial market volatility, as happened last August, but also to obstacles to the disinflation process, triggered by possible increases in commodity prices in the face of persistent geopolitical tensions, especially in the Middle East and Ukraine. According to the Fund, volatile commodity prices may lead to higher inflation, especially for commodity-importing countries, and limit central banks' room for manoeuvre. Weaknesses in China's real estate sector could also weaken consumer sentiment and bring negative spillovers on a global scale, considering China's primary role in world trade.

A risk factor is also the intensification of protectionist policies, which may increase trade tensions and hamper the functioning of supply chains; protectionism also risks weighing on the growth prospects of emerging and developing economies in the medium term, limiting the positive spillovers of innovation and technology transfer that have supported their growth since the onset of globalisation. All the more so in light of the outcome of the US elections on 5 November, this risk factor highlighted by the Fund is gaining in prominence.

Last but not least, let us take a look at international trade. According to IMF analyses, the ongoing tensions do not yet seem to have significantly impacted trade, which is expected to continue to grow in line with GDP developments in 2024-2025. However, signs of geo-economic fragmentation and friendshoring are beginning to emerge (see in this regard the article Challenges and changes in world trade): trade within geopolitical blocs thus seems to compensate for the increase in cross-border restrictions and the reduction in trade between distant geopolitical blocs.

Although fragmentation, when accompanied by an increase in intra-bloc trade, does not necessarily imply rapid deglobalisation, it may reduce the resilience of global supply chains and market efficiency, slow the transfer of knowledge between advanced and emerging and developing economies, and increase companies' costs and risks.