The United States and the balance of payments: a fragile balance

Published by Veronica Campostrini. .

Macroeconomic analysis Economic policy Trade balance United States of America Dollar Foreign market analysisThe Dollar as a Safe Haven Asset

From 1992 to 2024, the U.S. national debt experienced unprecedented growth. Yet, contrary to what one might expect, inflation remained relatively stable — averaging around 2.5% annually — with only occasional spikes.

As discussed in the article “Trump’s America and the Challenge to the Global Economic Order”, this apparent anomaly was made possible by a combination of factors: expansionary fiscal policy, deep domestic liquidity, and above all, a steady inflow of low-cost foreign goods that met internal demand without triggering significant inflationary pressure.

In this context, the cumulative balance of payments deficit surpassed $20 trillion. Yet, the dollar not only held its ground but even strengthened, cementing its role as a cornerstone of the global economy.

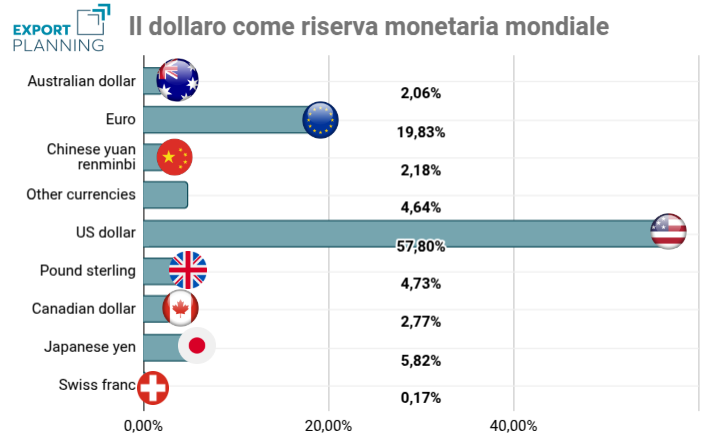

This paradox is explained by the dollar’s unique position as the world’s reserve currency, accounting for 58% of global foreign exchange reserves according to IMF data. Global demand for dollars — from central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and institutional investors — ensured a continuous inflow of capital into the United States, allowing it to finance chronic deficits without destabilizing its macroeconomic fundamentals.

The U.S. Dollar – An International Reserve

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations on IMF data

As we will explore in this article, the dollar’s role as a “safe asset” has enabled the U.S. to finance its current account deficit through offsetting movements in the financial account of the balance of payments, consistently attracting international buyers for its accumulated debt. The financial dynamics triggered by the so-called “Liberation Day” under the Trump administration clearly demonstrated how protectionist measures aimed at broadly reducing the current account deficit affect investor expectations, putting pressure on the balance mechanisms of these flows.

Tariffs and Financial Instability: A Boomerang Effect

The Trump administration’s introduction of tariffs was intended as a stimulus for the domestic economy. The stated goal was ambitious: to correct imbalances in the balance of payments by redirecting demand for goods from abroad to domestic production.

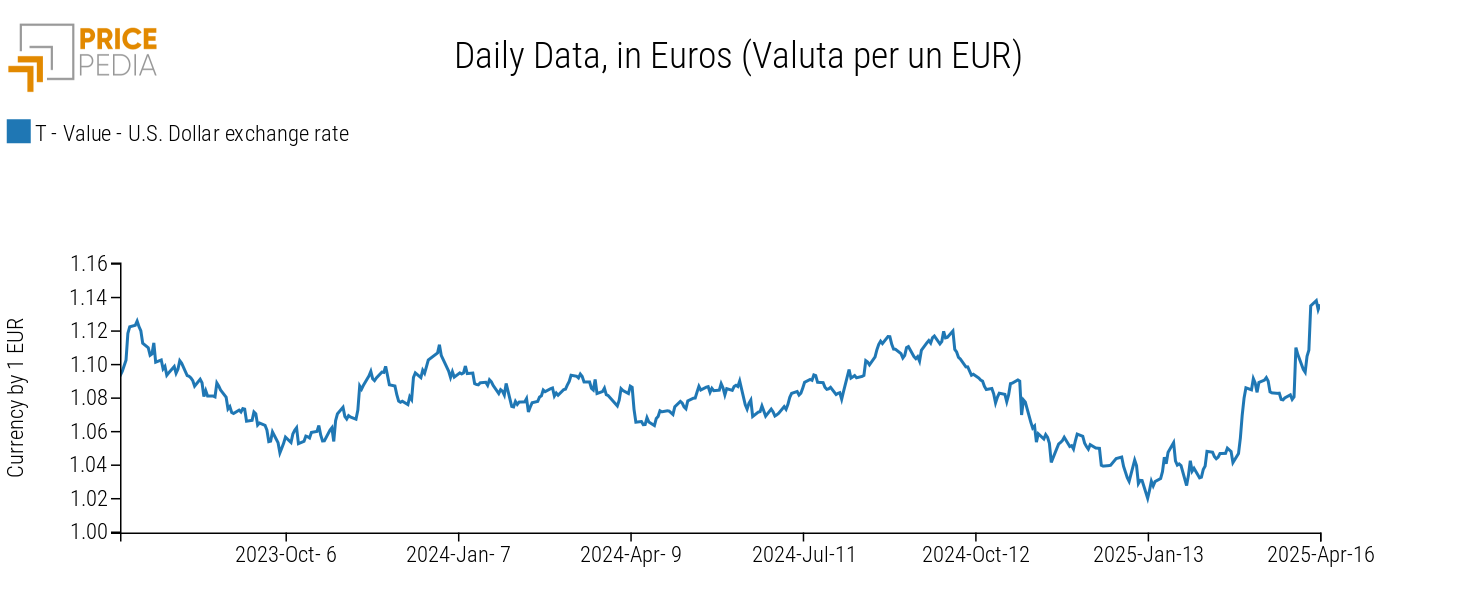

According to some analysts, a slowdown in foreign demand and a gradual shift back to domestic production could also have led to a progressive drop in interest rates, easing the burden of U.S. debt management. However, reality played out differently. The announcement of sweeping protectionist measures triggered an immediate reaction in financial markets — first through sharp stock market declines, then a spike in long-term yields on U.S. Treasury bonds, which neared 5%, and a depreciation of the dollar (as shown in the chart below).

USD Exchange Rate

Source: PricePedia elaborations

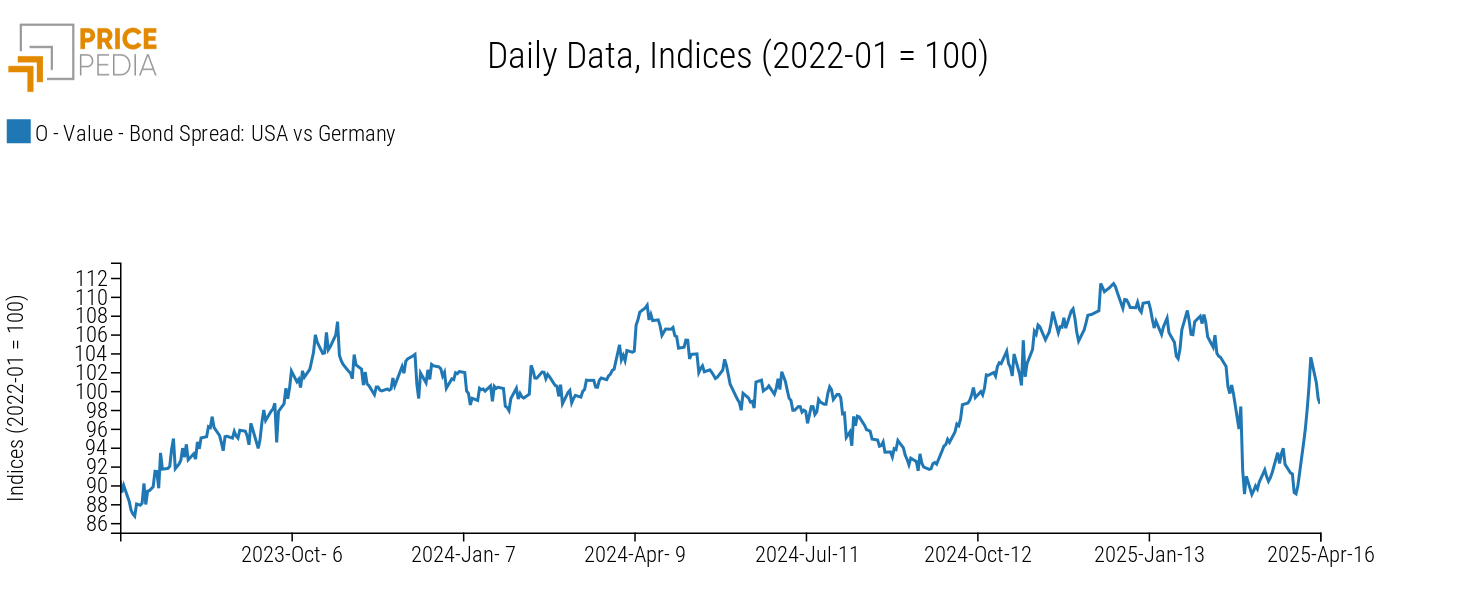

This yield spike is clearly visible in the spread between U.S. Treasuries and German Bunds (see chart below): starting April 2, the yield differential widened, signaling growing risk perception around American debt securities.

Bond Spread: USA vs Germany

Source: PricePedia elaborations

This chain reaction offers a structured lens through which to analyze how the balance of payments works, and how shifts in international investor expectations can lead to imbalances in a country's economic fundamentals.

The Balance of Payments: A Key to Understanding Imbalance

To fully grasp these dynamics, it’s essential to revisit the concept of the balance of payments — the accounting framework that records all transactions between a country and the rest of the world.

It consists of three main components:

- Current account: includes the balance of exports and imports of goods and services, along with income from capital and unilateral transfers.

- Capital account: records the movement of non-financial assets and capital transfers.

- Financial account: tracks inflows and outflows of capital and investments, including stocks, bonds, direct investment, and reserves.

By definition, the balance of payments is always in balance: a deficit in one component implies a surplus in another. However, the quality and nature of these flows determine the strength of that balance. The United States serves as a textbook example of this principle.

The U.S. Case: Structural Imbalances and Dependence on Foreign Capital

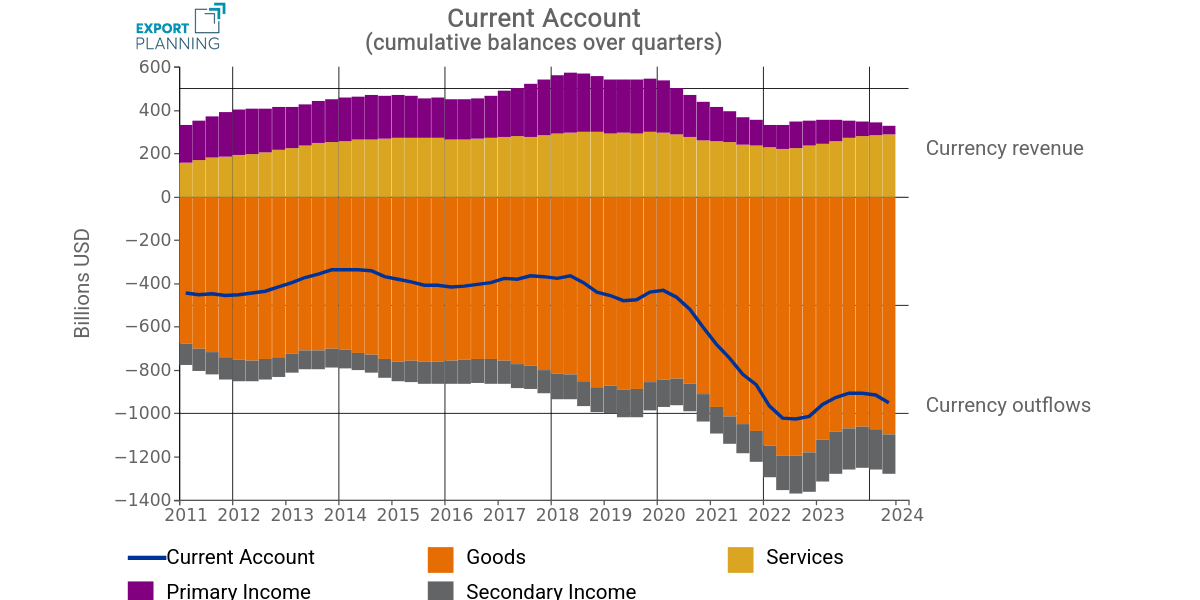

Current Account: The Chronic Deficit

The U.S. current account has consistently shown a negative balance, peaking above $1 trillion between 2022 and 2023. This deficit is largely driven by the trade imbalance in goods, which is not sufficiently offset by surpluses in services and capital income.

Balance of Payments: Current Account

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations

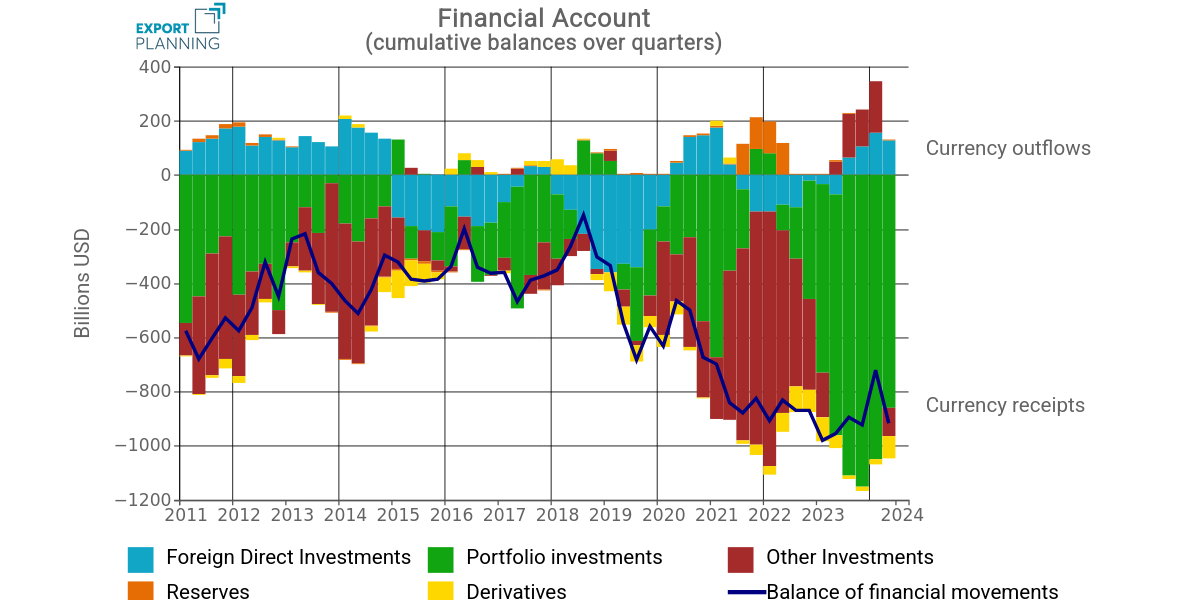

Financial Account: Capital Attraction and Risk

Over the years, the United States has managed to finance its current account deficit through debt issuance, which has always found international buyers — thanks to the appeal of stable returns and legal security.

However, this mechanism also leaves the U.S. economy exposed to sudden shifts in investor confidence.

Balance of Payments: Financial Account

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations

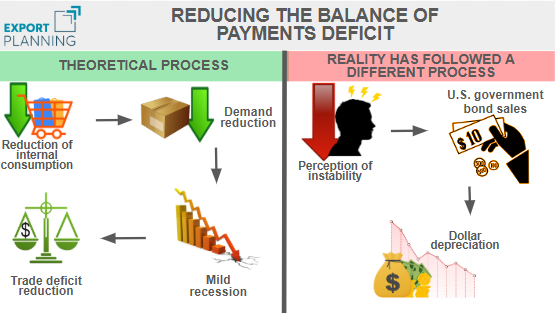

A Strategy That Didn’t Work

In theory, the imposition of tariffs could have followed a coherent macroeconomic logic: compress domestic demand to reduce the trade deficit and improve debt sustainability.

In practice, however, the announcements had the opposite effect, pushing up yields on U.S. debt instruments.

Reducing the BoP deficit

Source: ExportPlanning elaborations

Conclusions

Thanks to the dominant role of the dollar, the United States has long been able to finance its deficit without apparent consequences for its economic fundamentals. But how can this model be changed?

The attempt at rebalancing through protectionist measures revealed several critical issues in terms of financial market expectations, highlighting the limits of a unilateral approach in a globalized economy. Simply reducing imports is not enough to fix a structural deficit — it’s equally vital to preserve confidence, credibility, and the stability of the financial system.